Genode's VFS #2: Storage and interconnections

Over the past years, the Virtual File System (VFS) has played an ever more important role in Genode-based systems. Its applications cover not only access to conventional file systems but also font servers, network stacks, cryptographic devices, debugging facilities, and more. Yet documentation about the VFS is quite scattered and context-specific. In this article series I'd like to gather simple examples that explain how to use most of the plugins and utilities around Genode's VFS.

This article series is accompanied by a Github branch that contains several Genode scenarios for you to play around with. The scenarios are named repos/gems/run/vfs_example_x.run where x is the example number. I will refer to them as "example x" in the articles. If you don't know how to run Genode scenarios, please see the Genode Foundations book first.

These are all articles in this series so far:

Updates to this article:

-

2021-07-22, Martin Stein: Prevent term "ROM file", reference CBE article, describe <rump> plugin

Access to remote read-only files

A perfect warmup for persistent storage and interconnectivity with the VFS is the <rom> plugin (example 7):

<vfs> <dir name="friendly"> <rom name="greetings" label=""/> </dir> </vfs>

It causes the VFS to request a session of Genode's ROM service (which simply means access to a read-only file provided by another program) and provides local access to it through a VFS file. The label attribute determines the session label (in the context of the ROM service usually the name of the file at the server). The name attribute sets the name of the file in the local VFS. Let me add a server component that provides a file "greetings_rom":

<start name="dynamic_rom">

...

<provides><service name="ROM"/> </provides>

<config>

<rom name="greetings_rom">

<inline>Hello world!</inline>

...

</rom>

</config>

</start>

The dynamic ROM is normally used for read-only files whose content shall change over time, but it works for static files as well and I wanted to make the role of the service provider very clear. Because there is also another provider of the ROM service in example 7 that is not as visible: Genode's Core. Core's ROM service can be very helpful in combination with the VFS. It allows me to communicate host files to my Libc/POSIX application. With only some small changes to example 7 I can switch the server behind /friendly/greetings:

install_config {

...

<start name="vfs_example_7">

...

<route>

<service name="ROM" label="greetings_rom">

<parent/> <!-- the parent of this Init component is Core -->

</service>

...

</route>

</start>

...

}

# create host file

exec echo "Bonjour!" > bin/greetings_rom

# core will provide each boot-image module through its ROM service

build_boot_image { greetings_rom ... }

This demonstrates that the content of the local file /friendly/greetings depends on aspects outside the example program. First, on the decision of the Init program (the one that is configured via install_config) to which other component to route the ROM session request (configurable through the <route> tags) of vfs_example_7. And second, of course, on the behavior of that other component.

As you might have noticed, the example component used in this scenario is similar to that in example 4 from my last VFS article. Indeed, the only difference between example 4 and 7 is that, in the latter, I used the <rom> plugin instead of the <inline> plugin as back end for /friendly/greetings. This makes the lifetime and management of the file independent from the application. For the application code, however, the difference is transparent.

Mounting FAT file systems

The <fatfs> plugin first requests a "Block"-service session (access to a physical or virtual block device provided by another program, e.g., a device driver or emulating server). The block device behind this session is assumed to contain a FAT file system. Once the session has been established, the plugin will mount this FAT file system at that point in the local VFS where the plugin was loaded to.

Example 8 provides a simple scenario that demonstrates how this works. For emulating the block device, the scenario creates and formats a disk image on the host and adds it to the boot image (example):

dd if=/dev/zero of=bin/disk_image.hda bs=1024 count=65536

/sbin/mkfs.vfat -F32 -nlibc_vfs bin/disk_image.hda

build_boot_image { disk_image.hda ... }

This image is then provided through Core's ROM service. Next, the vfs_block component comes into play. This server can provide files from its local file system in form of a Block session to other components. In order to integrate the disk image into its VFS, I establish a session to Core's ROM service using the <rom> VFS plugin and copy the file to an in-memory file system using the <import> and <ram> plugins (see my last VFS article):

<vfs>

<ram/>

<import>

<rom name="disk_image_copy" label="disk_image"/>

</import>

</vfs>

Note that using the <rom> plugin alone as file back end would impede the writing direction at the provided block session. Therefore the copy. In order to grant permission for handing out a Block session to my application, I also have to add a corresponding policy:

<policy label_prefix="vfs_example_5" file="/disk_image_copy"

block_size="512" writeable="yes" />

The policy also contains the server-side parameters for the Block session. Now, in my application, the invocation of the FAT file system is very simple:

<vfs> <dir name="my_notes"> <fatfs/> </dir> ... </vfs>

Again, the application is the same as in an earlier example - example 5 to be specific. This earlier example created and modified a file inside an in-memory file system. The only difference now is that the <ram> plugin was replaced by the <fatfs> plugin, making my file persistent inside the disk image. You may check on this by removing the clean-up of the disk image at the end of the scenario and adapting the application to read the initial content of the file.

Mounting file systems using NetBSD rump

The <rump> plugin provides a rather peculiar way of integrating file systems. The plugin brings up a NetBDS rump kernel in order to host NetBSD file-system drivers. As back end, the plugin uses a Genode Block session just like the <fatfs> plugin. A typical integration of the <rump> plugin looks like this:

<rump fs="ext2fs" ram="10M"/>

The fs attribute defines the type of the file system on the block device. Possible values are cd9660 (ISO file system), ext2fs (ext2 file system), or msdos (FAT file system). The ram attribute sets the memory limit for the corresponding rump kernel and should therefore be chosen according to the RAM quota and usage of the component that contains the VFS.

There are good and simple examples on how to use the <rump> plugin among the standard tests of the Genode framework:

-

repos/dde_rump/run/rump_iso.run

-

repos/dde_rump/run/rump_ext2.run

-

repos/dde_rump/run/rump_fat.run

Therefore, I'll skip providing extra examples. From a user perspective, the plugin behaves the same as the <fatfs> plugin.

Mounting remote file systems

With the <fs> plugin, I can tell a local VFS to request a session of Genode's "File System" service and make this session accessible through a certain local directory. The difference to the above presented <fatfs> approach is that the File System session is a generic abstraction to file systems and, therefore, the management of the actual file system remains outside the application.

Example 9 demonstrates this. The scenario can be used only on a Linux host (using an x86_64 build directory and setting KERNEL=linux BOARD=linux). This is because it uses the lx_fs server, a component that makes the temporary Genode boot directory in this case <YOUR_BUILD_DIR>/var/run/vfs_example_9/genode) available to the running Genode scenario in the form of a File System service.

Like before, I have to acknowledge to the server that my application may open a session to his service:

<policy label_prefix="vfs_example_5" root="/" writeable="yes"/>

This time, I also have to state which sub-directory of the Genode boot directory will be the root of the file system provided to the client. With value "/", my application receives access to the whole boot directory.

Speaking of the application: It is the same as with the previous example. I merely replaced the <fatfs> plugin with the <fs> plugin. After running the scenario you may have a look at <YOUR_BUILD_DIR>/var/run/vfs_example_9/genode/entry_1 in your Linux host.

In this scenario, the Linux host was in charge of driving the file system, in contrast to example 8, where the application itself (better the <fatfs> plugin code inside the application) managed the FAT specifics. This introduces an important capability of the VFS in which the <fs> plugin plays a central role: Transparently switching between a local and a remote implementation approach. But to get really into this, another puzzle piece is missing.

Providing an individual VFS to other components

With the VFS server component, I can compose an individual local VFS with all plugins available and then provide it to other components via Genodes file system service. As you can see in example 10, the mechanism is very intuitive.

At my VFS server instance I assemble a VFS based on the servers own RAM and on services of other components I presented in former VFS examples vfs_block serving <fatfs>, dynamic_rom serving two instances of <rom>):

<vfs>

<ram/>

<dir name="my_dir">

<fatfs/>

<rom name="my_ro_state" label="remote_state"/>

</dir>

<import>

<rom name="my_rw_state" label="remote_state"/>

</import>

</vfs>

At this point please recall that <import> will create a writeable copy of the ROM session content in a file /my_rw_state in the <ram> file system and that <fatfs> and the other <rom> instance are getting stacked or overlayed inside /my_dir. In the next step, I add a policy that allows my example application to create a file system session to the root directory of the server's VFS:

<policy label_prefix="vfs_example_10" root="/" writeable="yes"/>

At the application, I can integrate the file system session using the VFS <fs> plugin again:

<start name="vfs_example_10">

...

<config> <vfs> <fs/> ... </vfs> ... </config>

<route>

<service name="File_system"> <child name="vfs"/> </service>

...

</route>

</start>

The application code can be divided into three steps. First, the writeable copy of the ROM session content (file /my_rw_state) is modified. Then, a new file is created in the FAT file system in /my_dir. And last, the test reads the original ROM session content via file /my_dir/my_ro_state and fails at writing to that same file.

Note that the effect of plugin stacking is well observable in this example. When asking, for instance, for /my_dir/my_ro_state, the VFS first pokes the <ram> file system. As the <ram> file system yet doesn't contain such file, it rejects the request. Next, the <dir> file system is asked. This one does know the directory at least (as it is the directory) and therefor goes on asking its sub-plugins <fatfs> and <rom> for the remaining path /my_ro_state. First, <fatfs> rejects for the same reason as <ram>. The <rom> instance, however, can finally contribute the leaf node of the path and finish the request.

Now, what would happen if, for instance, the <ram> file system also contained a file /my_dir/my_ro_state? In order to find that out, I simply add corresponding sub-nodes to the <import> plugin:

<import>

<dir name="my_dir">

<inline name="my_ro_state">Nothing here.</inline>

</dir>

...

</import>

With this, I can observe two changes in the test output:

... Read_bytes 0..12 of /my_dir/my_ro_state: "Nothing here." Wrote bytes 0..8 of /my_dir/my_ro_state Read_bytes 0..12 of /my_dir/my_ro_state: "Nice try.ere."

First, the file now contains the inline content instead of the content that is still propagated by the ROM service of dynamic_rom. Second, the file now appears to be writeable. So, what happend here? The new <import> sub-nodes tell the VFS to create and write a new file /my_dir/my_ro_state on application startup. Because of the plugin order, this request is first forwarded to the <ram> file system. As this plugin is very well capable of fullfilling the request, it creates the file and finishes the request. As a consequence of that future requests for /my_dir/my_ro_state wont reach any plugin beyond the <ram> FS as this one will now serve them. Thus, I successfully deactivated the <rom> version of the file by overlaying it with an ahead plugin.

If I were to put the <ram> instance below the <dir> FS, the writeable version of the file would end up in the <fatfs>:

<dir name="my_dir"> <fatfs/> <rom name="my_ro_state" label="remote_state"/> </dir> <ram/>

The test output remains the same but that the file is now stored inside the disk image outside the application. If I would also switch the order of <fatfs> and <rom>, however, the test output snaps back to the original:

<dir name="my_dir"> <rom name="my_ro_state" label="remote_state"/> <fatfs/> </dir> <ram/>

In this version, the <import> still ends up creating the file in the <fatfs> because the (first-asked) <rom> plugin rejects the request. But the <rom> plugin now has the "dominant" version of the file and thus /my_dir/my_ro_state provides the read-only ROM session content again.

Now, coming back to the VFS server as concept: What's the point of having an extra server to achieve something that I can also do application-local? At one hand, I prevent the application from having control over the file-system management. Or, viewed from another angle, I release the application from the complexity and details of the file-system management. Locally, all file access ends up at the the <fs> plugin and its file system session.

At the other hand, the VFS server can serve multiple clients at once. So, in contrast to an application-local VFS setup, I can access the same server-local VFS simultaneously from different programs.

Flexible componentization with the VFS

Let's now set the VFS server in the context of the ability of switching between local and remote implementations that I mentioned before. As I will demonstrate in later articles, I can implement really anything and make it accessible through a VFS plugin. This goes into the direction of the Unix-philosophy that everything is a file. Furthermore, VFS plugins can access the VFS they are in and therefore communicate among each other - an aspect that was visible already when the <import> plugin copied files to other VFS plugins.

That said, the VFS plugin concept becomes a generic approach to modularization. Imagine programming a bigger application and separating the different aspects of the program in different VFS plugins. Maybe I have some very application- specific code on top that is not in a plugin. But just as my VFS plugins communicate among each other using the VFS abstraction only, so does the top-level code when talking with the plugins.

In this situation, I could not only easily change the implementation of an aspect, but also where it is implemented. And, due to the nature of a VFS plugin, that is really only a dynamic library, I don't have to re-compile the application, the plugin, nor the server if I change the plugin location. It's all merely a matter of configuration.

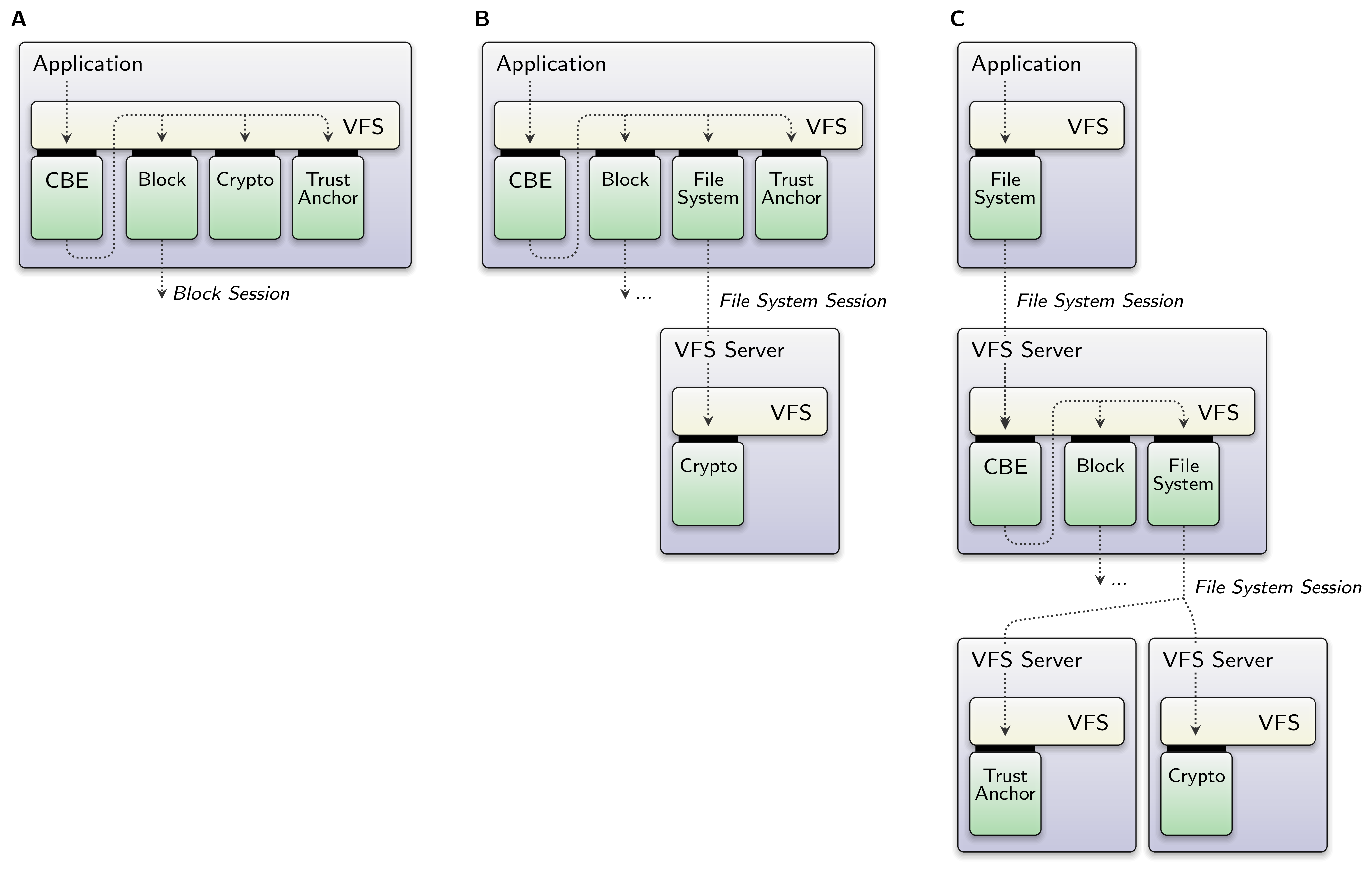

Let me give you a good real world example, but only on a very high level of abstraction. The VFS plugins of this example are yet to be explained in other articles but I think it's understandable without going into more depth. The CBE is a virtual block device that has block encryption and version control. On the VFS level, its functionality was split-up into the following aspects: a block-access back end (Block), a module for block encryption/decryption (Crypto), access to some sort of trust anchor device (Trust Anchor), and the core logic and front end of the virtual block device itself (CBE).

|

Depending on the individual context in which the CBE is used, maybe I don't want to mix the complexity of the application with the crypto algorithm (A) or even connect to a crypto device driver that provides a FS service instead of having a pure software solution. Or I might want to share one virtual block device among different clients (C) or have it all inside the one application because its a mere minimal demonstrator anyway (A). I don't have to settle on one version before integration - the code fits them all.

If you want to know more about the CBE, I took the picture from the Genode release notes 20.08. There you will also find references to all the other articles about the CBE.

Phew, this was a long article, but you made it :) I hope you enjoyed it as well. The next article will be shorter and about networking with the VFS.

Martin Stein

Martin Stein