Sculpt as a Community Experience

We just released the fourth version of Sculpt OS today. It is subtitled "Sculpt as a Community Experience". In this posting, I'd like to explain what's behind this slogan.

When I drafted the four stages of the road map of Sculpt one and a half years ago, I saw a vast design space in front of me. But the vision at the horizon was actually pretty clear: I wanted Sculpt to become an operating system that would scale beyond the limited capacities of our small company. With dread and awe, I looked how established operating-systems projects like the Linux kernel apparently master the coordination of a bee hive of developers, and I knew that I would never be up the such a task. With the goal of creating a sustainable OS, the only viable way forward would be the radical decentralization of responsibility.

I believed that Genode's dynamic component architecture puts an opportunity in front of me that does not exist anywhere else. In Genode, fundamentally, components can cooperate without mutually trusting each other. Could that premise be translated to the working of a developer community? If the system works well without the assumption that all important components are ultimately trustworthy, the user of the system does not need to trust each individual component provider either. For example, let's imagine a developer of a new wireless driver. In traditional OSes, such a driver has global reach within the system. If it is vulnerable, the whole system becomes vulnerable. For this reason, the driver developer must either be trustworthy, or the driver cannot reasonably be considered to be included in the OS. With Genode, this friction does not exist. The driver can see only the wireless card, and the wireless firmware is considered as untrusted anyway. Regardless of any potential malicious intent of the driver developer, the driver wouldn't be able to access the disk, capture the screen, or sniff key strokes. The driver is useful. We appreciate the developer's work. But we don't need to trust the developer. Let's face it, in current-generation systems, we don't trust the developers either. But we have to trust them.

The previous paragraph may have reminded you of academic fantasy from two decades ago. But in the real world, two open questions remained unanswered. First, how do the components end up at the computer of the user? And second, how can the user control the interaction of the components with one another? Sculpt CE provides answers to both questions.

Discovery, sandboxed installation, integrity protection

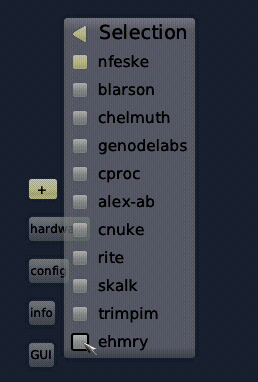

Every Sculpt system is equipped with a list of known software providers accompanied with their public keys and their download locations. Note that those providers don't need to be affiliated with Genode Labs. Also, the list can of course be customized by the user. The content obtained from each software provider resides in a distinct sub directory. The installation procedure facilitates Genode's fine-grained sandboxing such that content of one provider cannot interfere with the outside of its sub directory. When installing software, no global system state is changed. There are no install scripts whatsoever. The integrity of the content is protected by cryptographic signatures. So once installed, the user knows that the installed version corresponds bit-for-bit with the version as published by the software provider.

|

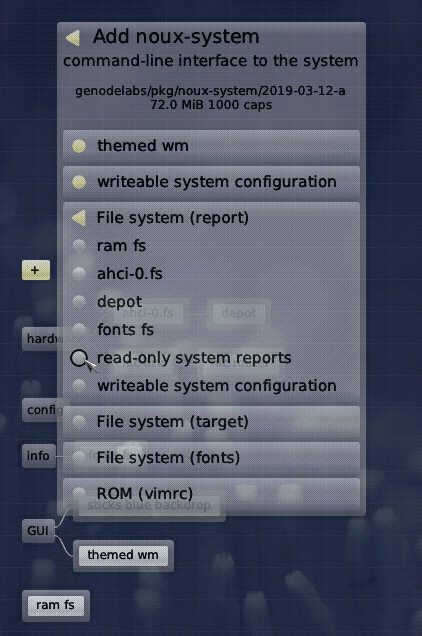

Each software provider known to the Sculpt system, may publish a digitally signed announcement of software packages. These so-called index files are like a catalogue of software. Sculpt CE provides the GUI depicted above for obtaining such catalogues, or to remove them. Once the index - the offering of the software provider - is available, the user can browse the catalogue and install components with a single click without fear. Once a package is downloaded, the user gets presented a dialog like this:

|

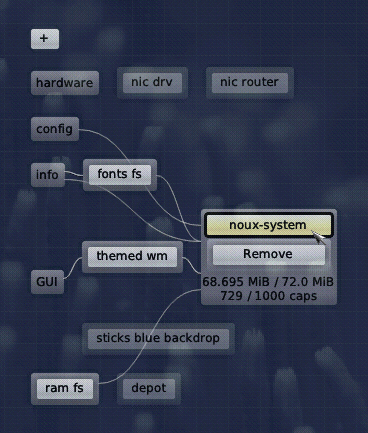

Here, the interplay of the new component with the rest of the system can be defined at a useful level of abstraction. The user's decisions comprise a whitelist of permissions. Since components can provide arbitrary services, this dialog allows the user to wire up not just the component with the underlying system but also with other components. The interplay between the components can be revealed at any time by selecting a component in the component graph:

|

The graph morphs into a view of the trusted computing base (TCB) of the selected component. All grayed-out components are outside the component's TCB and therefore uncritical. This tool enables the user to assess the potential reach of any deployed component. For example, the component selected above has no connection to the network. It is offline.

Where does it lead us?

The possible implications may be quite far-reaching.

As an immediate consequence of Sculpt's new software-provisioning model, the role of middlemen in-between the providers of software and the user - like app stores or distributions - is questioned. Sculpt empowers both the providers of software and the user, but independently from each other. A user can install and use components even without trusting the component provider in the first place because the interplay of each component with the rest of the system is completely under the control of the user, not the applications.

The second - the most anticipated but also the most unclear - potential effect is the friction-less scalability of the system and its developer community. For the first time, developers outside of Genode Labs can easily contribute to Sculpt OS, not only with new applications but with all kinds of typical operating-systems functionality, too.

The third implication is the inherent protection of users against malware by design. With each component subjected to the principle of least privilege, there is no place for malware to hide and to execute (of course, disregarding places that are outside the control of the operating system, like Intel ME).

As a fourth fascinating implication, the software-update treadmill that we experience with all commodity operating system of today is not needed any longer. Why would a user update a PDF viewer for security fixes when the PDF viewer has no disk or network access anyway? The user can break free from endless rhythm of system-global software updates!

Norman Feske

Norman Feske